The Lord passed before him and proclaimed, “The Lord, the Lord, a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness, 7 keeping steadfast love for thousands, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin, but who will by no means clear the guilty, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children and the children’s children, to the third and the fourth generation.”

The Lord passed before him and proclaimed, “The Lord, the Lord, a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness, 7 keeping steadfast love for thousands, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin, but who will by no means clear the guilty, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children and the children’s children, to the third and the fourth generation.”

— Exodus 34:6–7 —

Exodus 34:6–7 is one of the most important passages in the Bible. It’s also one of the more problematic. For how can God be gracious and compassionate, slow to anger and quick to forgive but also unwilling to forgive the guilty (“who will by no means clear the guilty, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children and the children’s children . . .”)? Doesn’t God’s self-revelation contain, at its heart, a significant contradiction?

Some have thought so, even solving the dilemma by debating the compositional history of Exodus 34, or denying its literary unity (see Ross Blackburn, The God Who Makes Himself Known, 155). But for those who read Exodus as God’s inspired Word, such critical workarounds don’t work. Thus, we must consider how God’s mercy and justice are not two opposing attributes that bring conflict into God’s character. Instead, they are two aspects of God’s undivided holy nature, which reveal themselves perfectly in God’s relationship with his creation.

On this subject Ross Blackburn has been helpful as he reads Exodus 34 in light of the whole canon, with special attention to Exodus 20:5–6. Following Blackburn’s canonical exegesis, we can press deeper into the nature of God’s holy character and then work forward in redemptive history to see how Exodus 34:6–7 informs God’s mercy and justice in places like Jonah 3–4 and Nahum 1, where Exodus 34 is in both books but in different ways towards the people of Nineveh. Continue reading

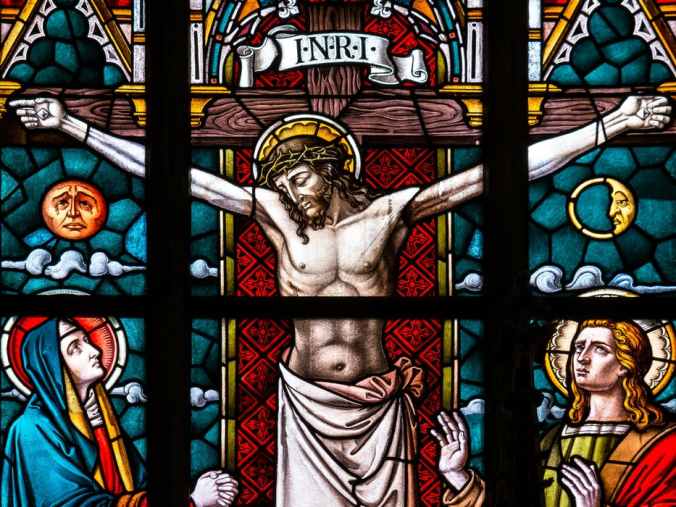

. . . they crucified him . . .

. . . they crucified him . . . As we prepare for Good Friday and Resurrection Sunday, consider this meditation from

As we prepare for Good Friday and Resurrection Sunday, consider this meditation from

In his excellent book

In his excellent book

“And whatever you ask in prayer, you will receive, if you have faith.”

“And whatever you ask in prayer, you will receive, if you have faith.”

In Ephesians 6:5–9 Paul finishes his “household codes” by addressing slaves/bondservants and masters and how they ought to work as unto the Lord. In fact, in five verses Paul makes five explicit references to Christ. Thus, as with marriage (Ephesians 5:22–33) and parenting (Ephesians 6:1–4), he gives hyper-attention to the way Christ motivates Christians in the marketplace.

In Ephesians 6:5–9 Paul finishes his “household codes” by addressing slaves/bondservants and masters and how they ought to work as unto the Lord. In fact, in five verses Paul makes five explicit references to Christ. Thus, as with marriage (Ephesians 5:22–33) and parenting (Ephesians 6:1–4), he gives hyper-attention to the way Christ motivates Christians in the marketplace.