In Genesis 6 we find the curious introduction to a group of people (?) called the Nephilim. In verse 4, the ESV reads, “The Nephilim were on the earth in those days, and also afterward, when the sons of God came in to the daughters of man and they bore children to them. These were the mighty men who were of old, the men of renown.”

In Genesis 6 we find the curious introduction to a group of people (?) called the Nephilim. In verse 4, the ESV reads, “The Nephilim were on the earth in those days, and also afterward, when the sons of God came in to the daughters of man and they bore children to them. These were the mighty men who were of old, the men of renown.”

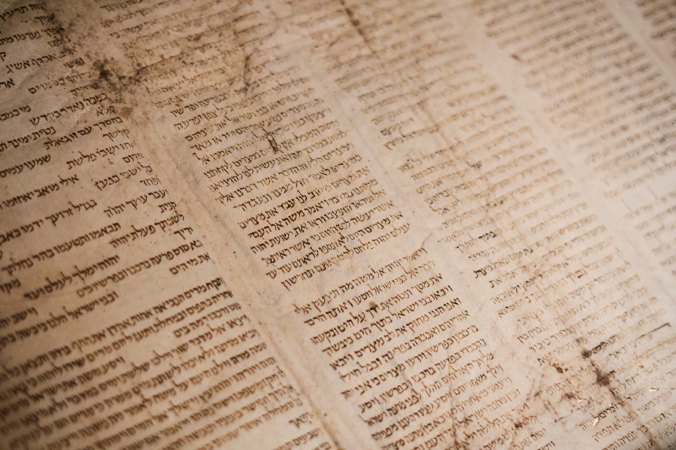

Thus concludes one of the strangest passages in all the Bible. For centuries, the four verses that begin Genesis 6 have occasioned debate on whom the Nephilim are, who the sons of God are, who the daughters of man are, who the mighty men of old were, the men of renown, and how these characters all fit together. Are these all descriptions of human beings, sons and daughters of Adam? Or, is something more nefarious afoot? Are the sons of God fallen angels? And if so, who are their offspring?

To these questions and more, I will attempt to give an answer in this post and three more to come. Below, I will consider what it means for Christians to use extra-biblical sources, and how we can properly benefit from reading 1 Enoch. In the next post, I will lay out the options for reading Genesis 6, and explain the strengths and weaknesses of various positions. Then third, I will make a canonical argument for understanding the sons of God as fallen angels and the Nephilim/mighty men as giants. Fourth, I will draw some theological conclusions related to Genesis 6 but also to Christ and his rule over the cosmos. Continue reading

Any time you read Revelation, it is like stepping out of reality and into a carnival of mirrors. Only those mirrors do not, or should not, reflect our own faces, so much as they reflect the prophets of the Old Testament, whose faces were reflected the glory of God’s Son.

Any time you read Revelation, it is like stepping out of reality and into a carnival of mirrors. Only those mirrors do not, or should not, reflect our own faces, so much as they reflect the prophets of the Old Testament, whose faces were reflected the glory of God’s Son.

In his

In his  By myself I have sworn; from my mouth has gone out in righteousness a word that shall not return: ‘To me every knee shall bow, every tongue shall swear allegiance.’

By myself I have sworn; from my mouth has gone out in righteousness a word that shall not return: ‘To me every knee shall bow, every tongue shall swear allegiance.’ 5 The aim of our charge is love that issues from a pure heart and a good conscience and a sincere faith. 6 Certain persons, by swerving from these, have wandered away into vain discussion, 7 desiring to be teachers of the law, without understanding either what they are saying or the things about which they make confident assertions.

5 The aim of our charge is love that issues from a pure heart and a good conscience and a sincere faith. 6 Certain persons, by swerving from these, have wandered away into vain discussion, 7 desiring to be teachers of the law, without understanding either what they are saying or the things about which they make confident assertions.