Sometime in seminary, my ecclesiology class was tasked with defining a biblical view of church polity. Here is that paper, refined and updated. It argues for an unmistakably Baptist reading of the Bible, as it conjoins congregational authority with elder leadership.

*******

Should the church be congregational or should it be led by a plurality of elders?

This oft-debated question finds its difficulty in the fact that both approaches find substantial biblical support. So the question, “What does the Bible say,” does not sufficiently lead to a one-sided resolution. To answer this question, the first thing that must be seen is the asymmetry implicit in the question. Congregationalism pertains to authority. Plurality of elders concerns leadership. Together, it is vital to recognize that authority and leadership are not synonymous, and that, in fact, God has wisely designed authority and leadership to be distributed through the church, even as the church recognizes and submits to appointed elders.

Therefore, even though many Baptist churches elevate congregationalism over, and at the expense of, elder leadership (i.e., congregational democracies) and other Presbyterian churches elevate elders over the congregation (i.e., elder ruled), it is best to have congregational authority and elder leadership, or so I will argue.

Congregational Authority

At first glance, congregationalism might be missed among the pages of the New Testament because its primary support is found in the structure of the New Testament, more than in the statement themselves. In other words, congregational authority is a presupposition (evident in the structure of the New Testament), more than a series of propositions (found in various proof-texts). Although, there are passages that support congregationalism, too. See, for example, Matthew 18:15–20; Acts 6:1–7; Acts 13:1–3; 1 Corinthians 5.

Before looking at those passages, however, consider the fact that Paul did not write a systematic theology or a confession of faith for the church. Instead, he wrote letters addressed to local churches. In fact, nine of his thirteen epistles were addressed to the believers gathered in places like Rome, Corinth, and throughout Galatia. And in each case, Paul addressed the whole church, not just those “in charge.” Although, he did recognize the overseers and deacons in places like Philippi.

As a result, Paul holds all members in the Galatian churches culpable for turning away from his gospel. Likewise, in his two letters to the Corinthians, he instructs the congregation on how to handle church discipline, not just the leaders. Following Jesus, he sees the congregation as the final line of authority (for church discipline, in this case).

Even in the Pastoral Epistles, Paul’s audience is intentionally wider than the person to whom he is writing. For instance, the whole congregation is held accountable for their doctrine and practice when he writes that the “household of God, which is the church of the living God, [is] a pillar and buttress of the truth” (1 Tim. 3:15). Each congregation was also responsible for evaluating the men in their midst who would be qualified to be elders or deacons.[1] And Jesus himself addressed the seven churches of Asia Minor in Revelation 2–3. Even if we interpret the word “messenger (angelos) of the church” (Rev. 2:1, 8, 12, etc.) as the leading pastor, not an angelic being, responsibility and repentance is a congregational matter.

More explicit rationale for congregational polity is also available. In Acts 6:1–6, it is the “full number of the disciples” who chose the seven men who would serve as deacons. This demonstrates the congregation’s role in electing their officers. Likewise, the qualifications for elders and deacons in 1 Timothy 3:1–13 are given to the whole congregation, so that they can appropriately select who will be their leaders (see also Titus 1:5–9). This begins to unveil the relationship between the congregation and the elders, a point of fact that is developed further in 1 Timothy 5, as Paul explains how the congregation should support the elder (vv. 17–18) and also hold them accountable (vv. 19–21).

As for Jesus, his teaching about church discipline further indicates that authority is vested in the congregation. The order of operations for church discipline in Matthew 18:15–20 gives the final decision to the local church. Not coincidentally, the keys of the kingdom are given to the church—not the pope, not the elders, nor any other administrative body (whether a presbytery or a third-party organization). And yes, this is the Baptist interpretation. Nevertheless, notice how the keys in Matthew 16:19 bind and loose on earth those things that are divinely decided in heaven, and how in Matthew 18:18–19 the congregation’s decision is an authoritative decision that mirrors (on the basis of Scripture) one’s status in heaven.

This type of logic is further delineated in 1 Corinthians 5. When Paul exercises his apostolic authority to instruct the church at Corinth, he charges the church to reinforce discipline/judgment. In addressing the situation of an unrepentant and undisciplined member of the church, he sharply rebukes the whole church to discipline this sexually immoral man. Concluding his argument, he asks, “Is it not those inside the church whom you (plural) are to judge” (1 Cor 5:12). Clearly, Paul sees the local church as the final authority to judge and make decisions.

Additionally, the doctrine of the priesthood of believers (plural[2]) gives theological warrant for congregational authority (1 Pet. 2:9). As all regenerate believers, young and old, are indwelt by the Holy Spirit (Eph. 1:13–14), equipped by the elders with the words of the apostles (Eph. 4:12), and have “the mind of Christ” (1 Cor. 2:16), they are ready together to exercise their God-given authority. In this way, each church member ought to play some part in the decision-making process within the local church, and those who are not ready to exercise such a role (i.e., young children) should not be admitted to membership yet.

This type of corporate interaction, where ideally every member is participating in the life of the church, helps mature individuals. And it helps congregations decide who is ready for membership. At the same time, this congregational model benefits the whole because each gifted member of the body exercises his or her gift for the edification of the body (Eph. 4:7–16).

With that said, the church cannot be a pure democracy, disregarding any sort of ordered leadership. While every member has a voice, not every voice can be equally influential. Those with greater understanding of God’s Word (Titus 1:9) should be leading the church (Heb. 13:7, 17). And hence, the faithful congregation appoints elders from who they can learn and to whom they must submit.

A Plurality of Elder-Leaders

While many modern churches lack a plurality of elders, it is an eminently biblical polity. And when rightly understand and applied, it is the best way to maintain the health and strength of the church. To see that, let’s consider a number of passages.

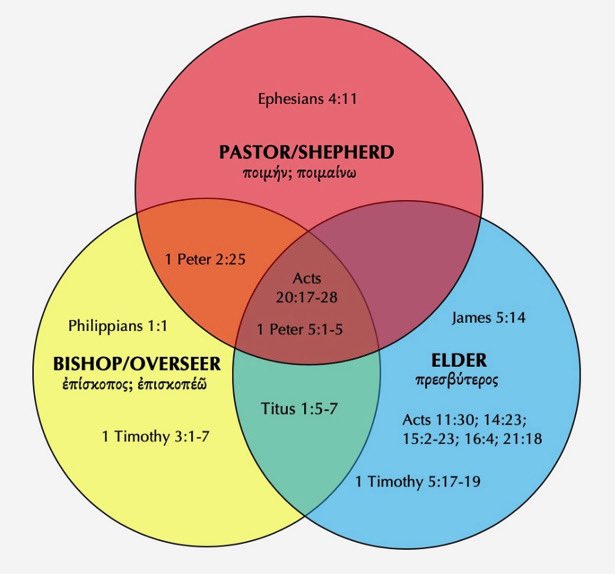

Beginning in Acts, Luke reports that Paul and Barnabas had appointed elders (plural) in every church (14:23). Likewise, Acts 20:17 speaks of “elders” as being synonymous with “overseers” in 20:28. In both cases there is a plurality of elders or overseers in a single church. As many have argued, the terms elder, pastor, overseer are synonymous terms for the same New Testament office.

Photo Credit: Colin Smothers via Denny Burk

Moving into the letters of Paul, it is obvious that plural leadership continues. Philippians 1:1 bears witness to the assumed roles of overseers and deacons in every church when Paul addresses his letter to “all the saints in Christ Jesus who are at Philippi, with overseers and deacons.” In Titus 1:5 Paul instructs Titus to appoint elders (plural) in every town (singular). Moreover, Paul instructs Timothy, his delegate to Ephesus, to “let the elders who rule well be considered worthy of double honor” (1 Tim. 5:17). To summarize, Paul instructs and assumes multiple elders to be appointed in every church.

The General Epistles reinforce this teaching, too. In the case of illness in the church, James 5:14 tells the elders (plural) to come to the aid of the sick congregant. Next, Peter explicitly instructs to elders in his first letter. Here the “fellow elder” addresses the “elders among you,” and proceeds to exhort them on how to serve as leaders within their church. Last, Hebrews 13:17 says, “Obey your leaders and submit to them, for they are keeping watch over your souls.” While presbyteros is not used in this passage, the plurality of church leaders remains.

Historically, Baptist churches have had a plurality of churches. Only in recent generations (the twentieth century) did that polity structure wane. In this post, I won’t get into the reasons, but my friend Jonathan Woodyard has a nice summary of the problematic trend.

Congregational Authority / Elder Leadership

When combining congregational authority and elder leadership, there are a number of intersections to cross. Space does not permit all of them, but let me offer a few reflections, beginning with a common, but shortsighted, approach to congregational polity from Baptist historian, James Leo Garrett.

Final human authority rests in the local or particular congregation when it gathers for decision-making. This means that decisions about membership, leadership, doctrine, worship, conduct, missions, finances, property, relationships and the like are to be made by the gathered congregation except when such decisions have been delegated to individual members or to groups of members.[3]

This straightforward definition nicely enumerates many of the areas where leadership is needed in the church. It also rightly puts final authority in the hands of the congregation. However, since Garrett stresses the leadership of the congregation as a whole, he unwittingly minimizes the place of elders in the life of the church. He rightly affirms the possibility of elder leadership (“delegated to individual members or groups of members”), but he overlooks God’s mandate that local churches are commanded to appointed qualified shepherds to lead them.

Distinguished from deacons, who assist the elders and typically meet the physical needs in the church, the elders (or pastors or overseers) are, in Garrett’s words, the “delegated individual members or groups of members” instituted by the New Testament. The only distinction to be made with Garrett—one that is sadly neglected in many churches—is that God himself “delegated” certain persons to lead the church. These are the gifted men of Ephesians 4:10–11 given to the church to equip the saints for the work of the service (v. 12) and the up-building of the body (vv. 13 – 16). While God doesn’t “name” these men in each local church; he does give qualifications in 1 Timothy 3 and Titus 1, so that local churches can identify their elders. Therefore, in every local congregation that aspires to be biblical, they must pray for, raise up, recognize, call, and submit to elders.

That said, how do elders relate to the congregation? First, the institution of elders does not remove the local church’s autonomy or corporate responsibility to govern themselves. Rather, God has graciously resourced his local churches with men who are called and equipped to lead the church. Therefore, even in congregational settings where discussion pertains to the often complex matters of “membership, leadership, doctrine, worship, conduct, missions, finances, property, relationships and the like,” there are godly leaders and teachers directing the whole congregation. They lead not by fiat but by teaching and establishing a biblical consensus. This is true shepherding and the plan for God’s local churches—elders who lead the flock by teaching; sheep who trust, follow, and esteem their leaders who give them the Word of God (Heb 13:7).

Accordingly, decisions in the church are not resolved through the casting of lots,[4] the contest of wills, or the embattlement of opinions in a business meeting free-for-all. Instead, all congregational decisions are superintended and presented by the governing elders, as the whole church supplies support and relevant information and counsel. This method preserves congregational polity, but always under the wise guidance of elders, men who are gifted to teach sound doctrine and reprove error.

Such a process moves the church slower than an elder-ruled or staff-directed church, because it requires the elders to lead a willing congregation. But that is the beauty of this system. God’s church is a flock, not a speedboat. As the elders painstakingly lead, teach, counsel, and correct, they gain the trust of their people, and thus the congregation functions (Lord willing) as a people who submit to their leaders, even while retaining their congregational authority.

From this brief survey, we have confidence to speak of the God’s design for a plurality of elders in the church. This is the leadership structure intended by God. But how does this structure relate to the church, to the congregation, and to the members of a local church? To those questions, we now turn.

The Congregation Delegates Authority to the Elders

The consistent testimony of the New Testament is that members of the church are to honor those who lead them (1 Thess. 5:12–13), even submitting to and obeying the leaders who taught them the Word of God (Heb. 13:7, 17). Those who are younger are to be “subject to the elders” (1 Pet. 5:5). Similarly, Paul identifies pastor-teachers as the ones who will equip the saints for the work of ministry (Eph. 4:12). The Apostle also commends faithful elders for ruling well, going so far as to call on churches to support them financially (1 Tim. 5:17). This clearly gives elders pride of place in teaching and ruling the local church. But does it give them authority over the church too?

As noted above, the keys of the kingdom, the symbol of heavenly authority, are given to the church. But this does not mean that a local church is a democratic community, where every member has the same knowledge of the truth. Rather, the gathered church has the authority and responsibility to recognize qualified men to be their elders, to call them to ministry, and then to submit to their teaching. In this way, when a church installs elders, they are delegating authority to those elders. This means that elders of a local church have a delegated authority to rule in that church. Individually, elders serve in that office when a congregation calls them to the office, and should that man disqualify himself, he can be removed from office too, just as 1 Timothy 5:19–21 indicates,

19 Do not admit a charge against an elder except on the evidence of two or three witnesses. 20 As for those who persist in sin, rebuke them in the presence of all, so that the rest may stand in fear. 21 In the presence of God and of Christ Jesus and of the elect angels I charge you to keep these rules without prejudging, doing nothing from partiality.

Importantly, as the elder is recognized by his individual character, so he is evaluated by his individual character, too. It is possible that multiple elders could simultaneously disqualify themselves, but in that case, each would have to be charged and found guilty. Equally, charges must be based on credible evidence from multiple witnesses and confirmed by an unwillingness to repent. As Paul puts it, if the elder persists in his sin, then his errors must be brought before the congregation.

At the same time, should he repent of his sin, that halts any type of church discipline. Yet, that repentance would then refer the question of elder qualification to the congregation. At that point, the question becomes: Is that man above reproach? Is the sinful action, now confessed and repented, disqualifying? To that question there are a host of particulars, but for our consideration here, the answer comes from the congregation. If the congregation has authority to call an elder, they also have the authority to remove an elder. Equally, they should be the body politic who receives an erring elder back into service. This both affirms the authority of the congregation and the supplies the elder with the confidence he needs to serve the local church.

Long story short, this particular path of elder confrontation and removal or restoration evidences the relationship between a church and her elders. Just as the elders are recognized by the congregation, so the elders remain in service as the congregation recognizes them as leaders. Equally, individual church members are called to submit the elders, and do not have individual authority over the elders, just as they do not possess an individual authority for themselves over against the church.

The congregation alone possesses an authority that exceeds the elders, but caution should be exercised if and when an individual or a small contingent in the church seeks to steer the whole church against all the elders. While it is possible that an entire elder board could be disqualified from service, the New Testament gives no such scenario. Rather, it provides many examples of leaders who have strayed from the doctrine or the ethical requirements of serving the Lord. There is no precedent for removing an entire elder council, and thus any kind of wholesale action moves forward without biblical support. Indeed, in such a case, removal of ever elder at one time would effectively decapitate a local church and render it vulnerable to the whims of the most powerful figures in the church. This type of action, attractive to some who would desire to reform the church into their image, should be avoided at all costs.

Biblical Congregationalism Respects Spiritual Maturity

On this point, let us take one more look at congregationalism. While authority lies in the entire body of the church, the local assembly is not an absolute democracy. The church is to be an orderly household, and just like a well-ordered home has a father who leads and instructs well, it also has children who submit to and obey their father. In the same way, babes in Christ ought to participate in the activities of the congregation, but with respect and submission to their fathers in the faith, and those who are their elder brothers in the church.

This in no way depreciates the congregational responsibility to govern its own affairs. Rather, it promotes an environment where spiritual maturity is fostered and church members follow the elders who lead them. It is God’s good design that younger believers should learn from their elders, so that over time younger men might be given opportunities to build up the church through their own giftedness, and women would do the same in their own ways (Titus 2:1–10).. Such a multi-generational church promotes godly character in the lives of church members (1 Tim 5:1–2), as the young learn to submit (1 Pet. 5:5ff) and the maturing grow in responsibility (1 Tim. 3:1–7, 1 Pet. 5:1–3). As Titus 2 teaches, the church is a family where the older teach the younger. This appreciation for age and wisdom (as well as spiritual maturity) puts the brakes on absolute democracy in the church, as well as individuals who think of themselves and their ministries more highly than they ought (Rom. 12:30. While the congregation does retain authority together; it’s family structure (i.e., “the household of God”), recasts the church in the light of family relations, not political power-plays. And in the household of God, the elders are authorized to equip those who are gifted for ministry, but also to withhold ministry opportunities from those who are not ready to serve.

Of course, this description is idealized. Sinful personalities and extra-biblical cultural dynamics will always encroach upon the “success” of this model. But again, with the checks and balances of God’s Word in place, the balance of congregational authority and elder leadership provides the best model for church life. It is designed to give oversight to the sheep who need leaders, without stripping these believers from the responsibility to grow and take ownership (in the right way) in their local church.

Experientially, every congregational/elder-led church will tend toward too much democracy in the congregation or too much power in the elders. Acknowledging this point, we are reminded that the system of government does not save. God does! Christ is building his church, and not men. Even more, we who lead and live in the community of the church must relentlessly depend on God for his grace to see our misguided and sinful tendencies and to correct them by the power of the Spirit and instruction of the Word.

An Association of Baptist Churches

Finally, we should consider the relationship of local churches, one to another. For unlike a Presbyterian hierarchy, Baptist churches believe that every church is locally governed and congregationally independent. This means that all associations with other churches are conducted on a voluntary basis.

Historically, Baptists have not understood the New Testament to implement a centralized authority or a body politic that stands over the local congregation. There are a couple reasons for this. First, looking at Acts 15, “there is not the slightest intimation that delegates went [to Jerusalem] from the other churches, which were now numerous, and scattered through different countries.”[5] J. L. Dagg’s point is that Scripture is silent about any sort of pre-established or emerging general assembly among the early Christians.

Second, even if a general assembly is conceded in Acts 15, the issue at hand is one concerning salvation. It occurred during a unique time in the church where apostolic authority was still setting the foundation for the church. The Jerusalem Council served as an instructive body for the early church and how Gentiles were to be grafted into that church. The meeting in Acts 15 was not convened to serve as a model for how church decisions were to be handled in coming generations.

Third, the genesis of the meeting came from Antioch not Jerusalem. In this way, it was not like James, bishop of Jerusalem, ordered the other churches to send delegates. Rather, in the period of the apostles, a question concerning grace, faith, circumcision, and the nations arose. Due to the confusion, Paul and Barnabas sought a decision from the apostles and elders of Jerusalem as to the message of the gospel. Thus, the situation in Acts 15 is unique, for today the gospel and its application to the nations is settled.

The source of authority for convening this council in Jerusalem comes not from a centralized ecclesial body; it actually comes from the authors of God’s Word. In this way, Acts 15 functions more like a return to the Bible than an assembly of church leaders. That is to say, Acts 15 teaches us not how to assemble the church, but how to interpret Scripture.

Nevertheless, the Bible does encourage awareness of and interaction between independent congregations. Paul encourages the church in Thessalonica because they are “an example to all the believers in Macedonia and Achaia” (1 Thess. 1:7). He implies other churches ought to replicate this faithful congregation. Likewise, Paul speaks more than once of the generosity of one church giving financially to another (Rom. 15:26–27; 2 Cor. 9:1–5; Phil. 4:14–19). In the same fashion, John speaks of how churches ought to receive traveling Christians from other churches (3 John 5–8). All of these references serve as examples of inter-church relations, of what has come to be known among Baptists as associationalism.

Local churches should partner with other local churches. Yet, with such a commitment to work with others, the establishment of authoritative bodies larger than the local church is extra-biblical. And while such a judiciary may at first appear to resolve numerous problems, it only creates others. And therefore, the final thing to say about elder-led congregationalism is that when troubles arise in the church, there is a place for receiving assistance from another local church. But it goes beyond the bounds of the New Testament to submit a local church to the authority of another church or another Christian ministry.

In Scripture, God has given us everything we need for life and godliness. And when it comes to the church, Scripture leads us to see that Jesus is present with his churches as churches (see Revelation 2–3). Moreover, he is content to confront churches as churches. And thus, it appears that outside arbitration should not be sought by the world (1 Cor. 6:1–8) nor by another church body (Acts 15). Instead, with the Word and prayer, repentance and repetition, the church gathers to be sanctified by the elders who preach the gospel and the Spirit who indwells the gathered saints.

Such are the means of grace that God gives in local churches. May we not treat them lightly or look to distort them. Instead, let us examine ourselves by the Word of God, so that we might be conformed into the image of Christ and that Christ might be formed in our local church.

Soli Deo Gloria, ds

Foundation stone, Muswell Hill Baptist Church by Christopher Hilton is licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.0

______________

[1]Even if Timothy and Titus appointed the first generation of elders, they would be dependent on the judgments of the local congregations. Likewise, since Timothy and Titus were apostolic delegates (not local pastors), their instructions were received so that the churches themselves would be able to recognize and appoint men to lead them. In this way, the authority to hold elders accountable rests finally in the congregation.

[2]Significantly, this doctrine affirms the corporate priesthood of believers (plural), not the priesthood of the believer (singular). The former rightly recognizes the authority invested in the local church; the latter unwittingly promotes the individual over the congregation and its elders. Although many (moderate and liberal and self-expressive) Baptists have advocated this doctrine, they have often done so erroneously—suggesting that “personal freedom” is a historic principle for Baptists.

In truth, the priesthood of believers affirms the dignity of the believer, as one of a company of priests. It does not follow, however, that every person has the autonomous freedom to do as they please. This runs into the problem of mutuality in the congregation and submission to the elders appointed in the congregation. In practice, a right understanding of the priesthood of believers is a healthy affirmation of congregational authority, but too often an unhealthy, headstrong priesthood of the believer (singular) is seen in congregational churches. Even worse is church filled with individual, self-authorizing priests, instead of a unified priesthood.

In the case of a priesthood of the believer, it should be recognized for what it is—an endorsement of self-centered human autonomy. Such self-willed Christianity is neither biblical, nor helpful. That said, we should not reject congregational authority, membership mutuality, and the priesthood of the believers, especially when united with respectful desire to submit to local shepherds—otherwise called pastor or elders.

[3]James Leo Garrett, “The Congregation-Led Church,” in Perspectives on Church Government (ed. Chad Owen Brand and R. Stanton Norman; Nashville: B&H, 2004), 157.

[4]The people of God at one time were forced to make decisions this way (Num. 27:21; 1 Sam. 28:6). Even before Pentecost and the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, the church made decisions by use of lots (Acts 1:26). But after the gift of the Spirit, the use of lots was no longer practiced.

[5]J. L. Dagg, Manual for Church Order (South Carolina: The Southern Baptist Publication Society, 1958; reprint, Harrisonburg, VA: Gano Books, 1990), 131.