In Matthew 5:17 Jesus says that he has not come to abolish the Law or the Prophets, but to fulfill them. And as D. A. Carson has observed about these verses, “The theological and canonical ramifications of one’s exegetical conclusions . . . are so numerous that discussion becomes freighted with the intricacies of biblical theology” (“Matthew,” 141).

In Matthew 5:17 Jesus says that he has not come to abolish the Law or the Prophets, but to fulfill them. And as D. A. Carson has observed about these verses, “The theological and canonical ramifications of one’s exegetical conclusions . . . are so numerous that discussion becomes freighted with the intricacies of biblical theology” (“Matthew,” 141).

In other words, it is really easy to import one’s biblical framework into Jesus’s words. For how one understands the law and its use in the New Testament and how the New Testament relates to the Old Testament, will in large measure impact the way one understands Jesus’s words, which in turn reinforces, or reforms, our biblical-theological framework.

Therefore, the question before is, “How do we stay on the line of Scripture when we interpret Matthew 5:17”? By comparison with Matthew 10:34 (“I have not come to bring peace, but a sword”) and Matthew 5:9 (“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God”), we learn that Jesus “non-abolishment clause” in Matthew 5:17 may not be absolute. Sharing the same structure as Matthew 5:17, Matthew 10:34 does not mean Jesus has forsaken his peace-making ways. Rather, his peace-making will include the restructuring (and severing) of family relations in order to make a new family of peace.

From this analogy, we learn there are some things in the Law that have come to an end—e.g., Hebrews indicates that Christ’s sacrifice ends the old covenant system of animal sacrifice. Therefore, we should go back to Jesus’s words to learn how to apply the Law. And thankfully, because of Matthew’s repeated and technical usage of the word “fulfill”/”fulfillment” (pleroō), we can get a good idea of how to understand the relationship of the Law to Christ and from Christ to us. Continue reading →

In Matthew 5:17 Jesus says that he has not come to abolish the Law or the Prophets, but to fulfill them. And as D. A. Carson has observed about these verses, “The theological and canonical ramifications of one’s exegetical conclusions . . . are so numerous that discussion becomes freighted with the intricacies of biblical theology” (“

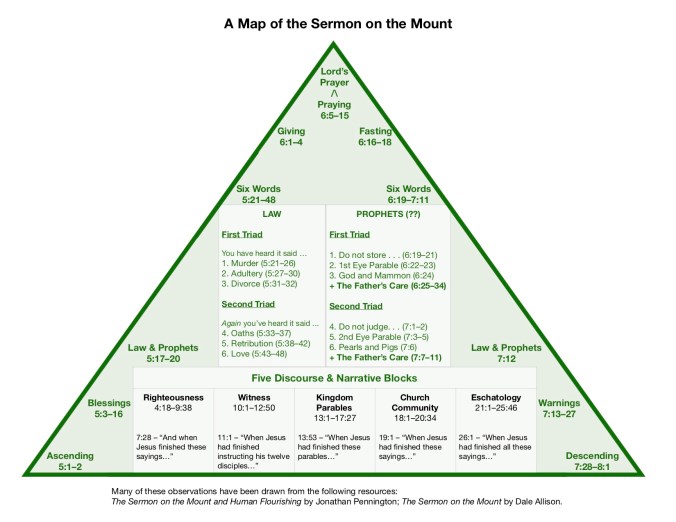

In Matthew 5:17 Jesus says that he has not come to abolish the Law or the Prophets, but to fulfill them. And as D. A. Carson has observed about these verses, “The theological and canonical ramifications of one’s exegetical conclusions . . . are so numerous that discussion becomes freighted with the intricacies of biblical theology” (“ What is the Sermon on the Mount about? And more basically, what is the Sermon on the Mount? Is it a newer, more stringent law for Christ’s disciples? Is it an ideal which drives disciples to seek mercy? How should we understand it?

What is the Sermon on the Mount about? And more basically, what is the Sermon on the Mount? Is it a newer, more stringent law for Christ’s disciples? Is it an ideal which drives disciples to seek mercy? How should we understand it? When reading Matthew 5:21–26, the first of six illustrations from Jesus on how to read and apply the Law of Moses, there are a number of interpretive factors to consider. In fact, we need to consider the meaning of the “anger,” the relationship of the Law-covenant to the Jesus’s fulfillment, and the way Jesus employs imagery from the first recorded murder.

When reading Matthew 5:21–26, the first of six illustrations from Jesus on how to read and apply the Law of Moses, there are a number of interpretive factors to consider. In fact, we need to consider the meaning of the “anger,” the relationship of the Law-covenant to the Jesus’s fulfillment, and the way Jesus employs imagery from the first recorded murder.