Imprecatory psalms (e.g., Pss 5, 10, 17, 35, 58, 59, 69, 70, 79, 83, 109, 129, 137, 140) are those psalms which call upon God to destroy the enemies of God. They come from the anguished hearts of persecuted Israelites, and they include some of the most shocking words in the Bible. Take just a few examples.

Imprecatory psalms (e.g., Pss 5, 10, 17, 35, 58, 59, 69, 70, 79, 83, 109, 129, 137, 140) are those psalms which call upon God to destroy the enemies of God. They come from the anguished hearts of persecuted Israelites, and they include some of the most shocking words in the Bible. Take just a few examples.

Psalm 35 provides one of the most acceptable imprecatory Psalms. Verses 4–6 read,

Let them be put to shame and dishonor

who seek after my life!

Let them be turned back and disappointed

who devise evil against me!

Let them be like chaff before the wind,

with the angel of the LORD driving them away!

Let their way be dark and slippery,

with the angel of the LORD pursuing them!

(Psalm 35:4–6)

In Psalm 109, the language gets more severe as David calls for the personal ruination of the wicked.

Appoint a wicked man against him;

let an accuser stand at his right hand.

When he is tried, let him come forth guilty;

let his prayer be counted as sin!

May his days be few;

may another take his office!

May his children be fatherless

and his wife a widow!

May his children wander about and beg,

seeking food far from the ruins they inhabit!

May the creditor seize all that he has;

may strangers plunder the fruits of his toil!

Let there be none to extend kindness to him,

nor any to pity his fatherless children!

May his posterity be cut off;

may his name be blotted out in the second generation!

May the iniquity of his fathers be remembered before the LORD,

and let not the sin of his mother be blotted out!

Let them be before the LORD continually,

that he may cut off the memory of them from the earth!

(Psalm 109:6–15)

Finally, in Psalm 137 David pronounces a benediction on those who destroy the children of the wicked:

Remember, O LORD, against the Edomites

the day of Jerusalem,

how they said, “Lay it bare, lay it bare,

down to its foundations!”

O daughter of Babylon, doomed to be destroyed,

blessed shall he be who repays you

with what you have done to us!

Blessed shall he be who takes your little ones

and dashes them against the rock!

(Psalm 137:7–9)

Due to their graphic violence and divine approval—they are in the Bible, after all—many Protestant liberals have charged the God of Israel with violence unbecoming a deity. Other modern readers have written off Christianity entirely because of the imprecatory Psalms and Israel’s violent history. Even for gospel-loving, grace-proclaiming Christians, the inspired cries for vengeance make us feel uncomfortable. They don’t immediately fit our normal grid for a God who is love. What, therefore, should we think about the imprecatory Psalms?

A few years ago, my PhD Supervisor and good fried, Stephen Wellum, gave a Sunday School lesson on these psalms, and what follows is an amplified outline of his lesson. Continue reading →

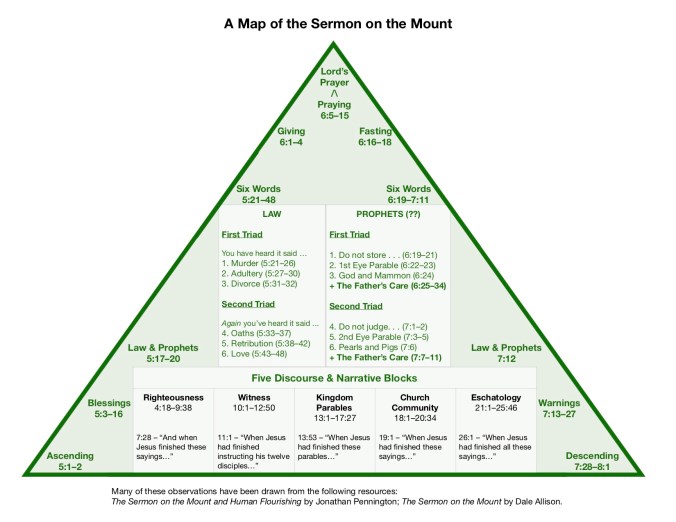

In the middle of the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus gives instructions about giving (vv. 2–4), praying (vv. 5–15), and fasting (vv. 16–18). In our church we have taken one sermon per “spiritual discipline,” but really in the structure of Matthew’s Gospel, we should read these three disciplines together. And in fact, when we do there are some observations we discover that we might not find on our own.

In the middle of the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus gives instructions about giving (vv. 2–4), praying (vv. 5–15), and fasting (vv. 16–18). In our church we have taken one sermon per “spiritual discipline,” but really in the structure of Matthew’s Gospel, we should read these three disciplines together. And in fact, when we do there are some observations we discover that we might not find on our own.

Imprecatory psalms (e.g., Pss 5, 10, 17, 35, 58, 59, 69, 70, 79, 83, 109, 129, 137, 140) are those psalms which call upon God to destroy the enemies of God. They come from the anguished hearts of persecuted Israelites, and they include some of the most shocking words in the Bible. Take just a few examples.

Imprecatory psalms (e.g., Pss 5, 10, 17, 35, 58, 59, 69, 70, 79, 83, 109, 129, 137, 140) are those psalms which call upon God to destroy the enemies of God. They come from the anguished hearts of persecuted Israelites, and they include some of the most shocking words in the Bible. Take just a few examples. There are many arguments for reading the Bible with Christ at the center. But where do they come from? Are they the product of biblical interpreters? Or is there a source found in Scripture itself?

There are many arguments for reading the Bible with Christ at the center. But where do they come from? Are they the product of biblical interpreters? Or is there a source found in Scripture itself?

In Matthew 5:17 Jesus says that he has not come to abolish the Law or the Prophets, but to fulfill them. And as D. A. Carson has observed about these verses, “The theological and canonical ramifications of one’s exegetical conclusions . . . are so numerous that discussion becomes freighted with the intricacies of biblical theology” (“

In Matthew 5:17 Jesus says that he has not come to abolish the Law or the Prophets, but to fulfill them. And as D. A. Carson has observed about these verses, “The theological and canonical ramifications of one’s exegetical conclusions . . . are so numerous that discussion becomes freighted with the intricacies of biblical theology” (“ Hunger. It’s one of the most basic of human desires. And in the Bible it is one of the most important concepts related to salvation, faith, and one’s experience with God.

Hunger. It’s one of the most basic of human desires. And in the Bible it is one of the most important concepts related to salvation, faith, and one’s experience with God.