Both James Jordan and Alistair Roberts have made a case that the literary structures of Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 mirror one another.[1] As evidenced in Genesis 1:1–2:3, creation took place over the course of seven days—six days of work, one day of rest. Equally, Genesis 2:4–25 follows a similar pattern, as observed below, as does Genesis 3, which Jordan develops in his book Trees and Thorns: Studies in the First Four Chapters of Genesis.

If this reading is correct, then the first three chapters of Genesis give us three parallel events—three weeks that speak of the same creation week. To put it in temple terms, Genesis 1 gives us the creation of the macro-temple, the cosmos; Genesis 2 gives us the formation of the micro-temple, the garden; and Genesis 3 gives us the defilement of the garden which leads to the de-creation of the cosmos, what I might call the massacred-temple.

If this approach is correct, then it not only stresses the seven day pattern of creation, with each chapter following the same basic pattern (see below). But it also situates the first three chapters as following.

- Genesis 1 outlines the full, seven-day creation week (Gen. 1:1–2:3),

- Genesis 2 returns to Day 6 to detail how God created man at the beginning of the day and woman at the end of the day (Gen. 2:4–22),

- Genesis 2:23–25 develops the glory of God’s good creation, as the woman comes to the man when he awakes on Day 7. But it continues to watch that glory turn to shame, as the rest of Day 7 follows the tragic sin of humanity to believe the serpent, eat the fruit, and rebel against God. As a result, man’s first disobedience results in him being cut off from the Tree of Life (Gen. 3:1–24; cf. Rom. 5:12, 18–19).[2]

Following Jordan and Roberts, therefore, I offer the following seven day outline of Genesis 1–3. Let me know what you think and how it might be improved. At the end, I’ll share why reading these chapters in this way matters. Continue reading

Now Barnabas wanted to take with them John called Mark. But Paul thought best not to take with them one who had withdrawn from them in Pamphylia and had not gone with them to the work. And there arose a sharp disagreement, so that they separated from each other. Barnabas took Mark with him and sailed away to Cyprus, . . .

Now Barnabas wanted to take with them John called Mark. But Paul thought best not to take with them one who had withdrawn from them in Pamphylia and had not gone with them to the work. And there arose a sharp disagreement, so that they separated from each other. Barnabas took Mark with him and sailed away to Cyprus, . . .

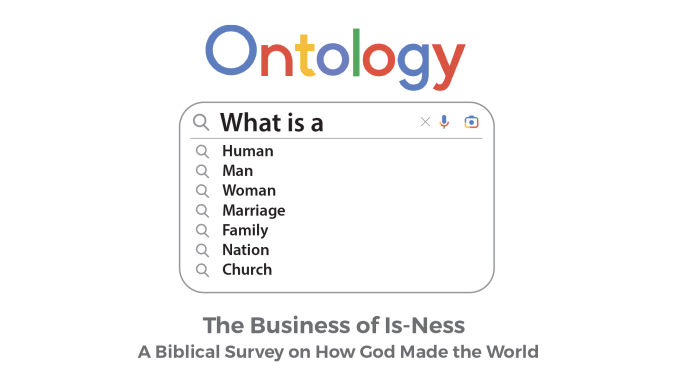

Since 2013, I have taught the doctrine of humanity a half a dozen times. And in each class, I have put this question on the final exam: What is the most important doctrine for the twenty-first century?

Since 2013, I have taught the doctrine of humanity a half a dozen times. And in each class, I have put this question on the final exam: What is the most important doctrine for the twenty-first century? Last year, I joined Nicholas Piotrowski, Charles Ware, and Gus Pritchard for an event in Indianapolis called “

Last year, I joined Nicholas Piotrowski, Charles Ware, and Gus Pritchard for an event in Indianapolis called “ Last year I wrote a

Last year I wrote a  A number of years ago, a church I know purchased something like 100,000 copies of the Gospel of John. Why? So that they could share the message of salvation with everyone in their Chicago suburb. That is to say, by putting a copy of John’s Gospel in everyone’s mailbox, they hoped to share the good news of salvation with all their neighbors.

A number of years ago, a church I know purchased something like 100,000 copies of the Gospel of John. Why? So that they could share the message of salvation with everyone in their Chicago suburb. That is to say, by putting a copy of John’s Gospel in everyone’s mailbox, they hoped to share the good news of salvation with all their neighbors. Consider Jesus.

Consider Jesus.