How should we understand the earth-shaking, temple-making promises of Haggai 2?

How should we understand the earth-shaking, temple-making promises of Haggai 2?

Twice in this short book, “Haggai the prophet” announces that heaven and earth will be shaken by the Lord (2:6–7 and 2:21) and that on the other side of this cosmos-shaking event (or events), the Lord will establish a greater temple (2:9) and restore hope for David’s throne (2:22–23). Because of the apocalyptic nature of these words, some have seen in them a prediction for a future millennial temple. For instance, Mark Rooker says when addressing the temple in Ezekiel 40–48, “Similar references to a temple in the messianic kingdom include Isaiah 2:2–4 and Haggai 2:9” (A Case for Premillenialism, 130–31). Likewise, David Turner writes,

The prophet Haggai alludes to the fact that this temple was unimpressive when compared with the first. However, the word of the Lord confirms to Zerubbabel the promise that God is with the nation. With words that anticipate Revelation 21:24–26 and 22:2, Haggai 2:6–9 promises that God’s judgment of heaven and earth (cf. Heb. 12:26) will result in the nations’ bringing their glory to the temple. Thus its latter end will be characterized by a greater peace and glory than that of the first temple. (David L. Turner, “The New Jerusalem in Revelation 21:1–22:5,” in Dispensationalism, Israel, and the Church, 269).

Interestingly, none of the big books of dispensational eschatology that I have on my shelf (e.g., Millennialism: The Two Major Views by Charles L. Feinberg; Things to Come by J. Dwight Pentecost; Christ’s Prophetic Plans by John MacArthur and Richard Mayhue; The Case for Progressive Dispensationalism by Robert Saucy) address Haggai exegetically. Pentecost lists Haggai 2:1–9 as one of the passages he will later expound on the concept of God’s kingdom in the Old Testament (442), but he never returns to this passage. In fact, the most comprehensive exegetical statement I’ve found on Haggai is contained in the MacArthur Study Bible, where the comments interpret Haggai as testimony to a millennial kingdom with a rebuilt temple. Here are two examples.

2:6, 7 I will shake. The shaking of the cosmic bodies and the nations goes beyond the historical removal of kingdoms and the establishment of others, such as the defeat of Persia by Greece (Dan. 7). Rather, the text looks to the cataclysm in the universe described in Rev. 6–19, the subjugation of the nations by the Messiah, and the setting up of His kingdom which will never be destroyed (cf. Dan. 2:44; 7:27; Zech. 14:16–21; Matt. 25:32; Luke 21:26; Heb. 12:26; Rev. 19:19–21). (1334)

2:9 this latter temple. The Jews viewed the temple in Jerusalem as one temple existing in different forms at different times. The rebuilt temple was considered a continuation of Solomon’s temple (cf. v. 3). However, the eschatological glory of the millennial temple, i.e., the latter temple, will far surpass even the grandeur of Solomon’s temple (the former temple). I will give peace. This peace is not limited to that peace which He gives to believers (e.g., Rom 5:1), but looks ahead to that ultimate peace when He returns to rule as the Prince of Peace upon the throne of David in Jerusalem (Is. 9:6–7; Zech 6:13; Acts 2:30). (1335)

From these comments, we get a clear perspective of a dispensational reading of this passage. But is that the best reading? Should we conclude that Haggai, dated to 520 BC in the second year of the reign of Darius (1:1), is talking to the people of Israel about a future kingdom and temple that comes on the other side of the messiah, whose kingdom they have not yet seen or understood? I don’t think so, and in what follows I will aim to provide an interpretation of Haggai 2 that pays closer attention to the historical context of his message and the canonical message of the kingdom of God come in the person and work of Jesus Christ.

In other words, instead of constructing a brick and mortar temple in the future with the words of Haggai, we should see how his words speak to the remnant addressed in his book (1:12, 14; 2:2) and then how they speak to the people on whom the end of the ages has come (1 Corinthians 10:11). Continue reading →

I am concerned that currently evangelical theology is not doing a very good job with the cross of Christ. Why do I say that? Because some of the most popular works on the cross of Christ are distorting, denying, or just plain ignoring the penal substitutionary nature of the atonement.

I am concerned that currently evangelical theology is not doing a very good job with the cross of Christ. Why do I say that? Because some of the most popular works on the cross of Christ are distorting, denying, or just plain ignoring the penal substitutionary nature of the atonement.

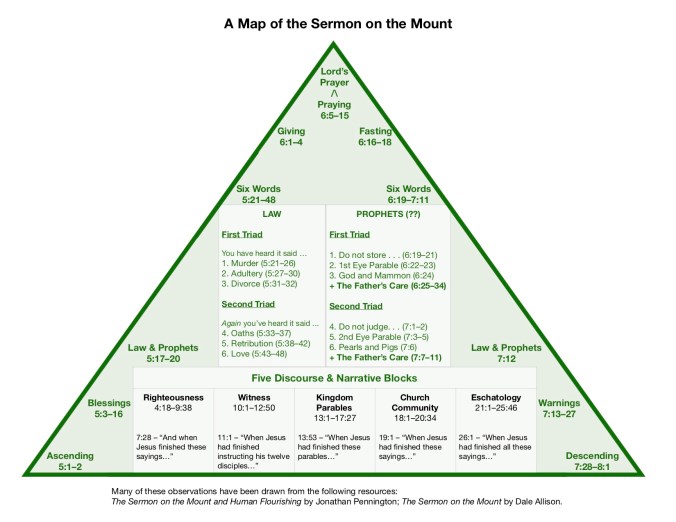

The Sermon on the Mount is probably the most famous sermon ever preached, and for good reason. Its speaker is the Lord Jesus Christ; its location on a hill overlooking the Sea of Galilee is unique; and its language is both beautiful and profound. Even non-believers are familiar with many of the words Jesus spoke in this sermon.

The Sermon on the Mount is probably the most famous sermon ever preached, and for good reason. Its speaker is the Lord Jesus Christ; its location on a hill overlooking the Sea of Galilee is unique; and its language is both beautiful and profound. Even non-believers are familiar with many of the words Jesus spoke in this sermon. Earlier this

Earlier this  In his theological commentary on the Sermon on the Mount,

In his theological commentary on the Sermon on the Mount,

How should we understand the earth-shaking, temple-making promises of Haggai 2?

How should we understand the earth-shaking, temple-making promises of Haggai 2? The

The